How it all began -

RC Farms Sweet Chestnuts, McMinnville, OregonWhen Columbus discovered America, the principal native timber was chestnut. When the earliest settlers came to the East Coast, they made log cabins and fences principally from chestnut – a long-enduring, termite-proof wood.

Nuts from the majestic spreading 100-foot tall trees were nourishing food for pioneers – vital for surviving the winter. Chestnuts were used for the livestock, for hog feed. Deer and other wild animals depended on them. Chestnuts were as common – almost as routine in the diet – as milk.

Over the decades, the all-American scene moved on: “chestnuts roasting on the open fire”; chestnut stuffing for Thanksgiving as traditional as cranberries. Vendors sold roasted chestnuts on eastern city streets. And as America’s pot began to meld and Asians and Europeans came to America, they brought with them their culture’s appreciation for the nuts. All this mostly enbeknownst to westerners.

Then came a true biological disaster – the loss of that area’s major forest tree – a disaster with considerable economic consequence.

It came about, some say, in the early 1900s before the days of quarantine, when a Chinese chestnut was brought to New York to be planted in a park. That tree introduced chestnut blight to those East Coast chestnuts. During the next several decades, that blight decimated America’s entire chestnut industry.

Meanwhile, on the West Coast about 10 years ago, Randy Coleman was attending ag shows and availing himself of the reams of material offered at such. He collected information on chestnuts. “I read that millions of pounds of chestnuts were imported to the U.S. every year – and none were grown here. That’s an awful lot of any product and it caught my attention,” he said. “Chestnuts could be grown in McMinnville. Further, the East Coast industry never rebounded – perhaps in part because growers were leery of being wiped out by that blight.”

So Randy, who had never eaten a chestnut and didn’t know what they looked like, became a chestnut grower. About 10 years ago he started planting.

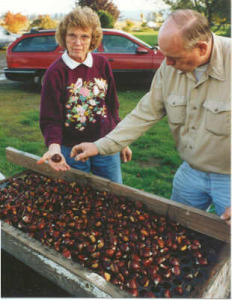

Back In 1985, Randy and Irene Coleman, were the first growers to plant a commercial crop in the valley. They now have 14 acres in production close to their home on Oregon 99W.

Unlike other nuts, chestnuts are picked several times, about every three days.

“You have to let them fall naturally so they’ll come out of the burr,”

Randy Coleman is a third-generation McMinnville-area farmer who specialized in broccoli, cauliflower and green beans and was “looking for something different” when he read that “hundreds of thousands of pounds of chestnuts are imported into the U.S. every year.”

The native chestnut trees, which composed the bulk of North American hardwood forests when the Europeans first arrived, were wiped out by blight during the early part of this century.

Thus generations of Americans have never seen a chestnut tree and wouldn’t have tasted chestnut dressing in their Thanksgiving turkeys were it not for the imported varieties.

“They may be unknown to us, but we’re importing them for somebody,” Coleman recalled thinking during his quest for an alternative crop. It sounded simple. Grow chestnuts and it’d be “just a case of them buying from us.”

In the late 1980s, Coleman embarked on a research expedition to California where the chestnut growers he met “were kind of tight-lipped. They didn’t share a lot of information with me.” He decided to return to Oregon via a different route, and on the way home stopped in Placerville, Calif., where he serendipitously discovered Bob Bergantz.

Coleman spent two days with Bergantz and his wife, custodians of the few notes and chestnuts that were left after a greenhouse fire destroyed the work that created the Colossal chestnut hybrid.

On the second day of his visit, Coleman recalled, Bergantz and his wife, who were both in their 80s, “went into another room and when they came out, they had decided I was to be the anointed one.”

Coleman, who’d originally planned to plant 100 acres in chestnuts, returned to Oregon with 100 Colossal chestnuts and a scaled-down plan.

The Colemans planted their first orchard, four acres, in 1988. Three years ago, another 10 acres went in.

“At the time I started, total chestnut acreage in the United States was 50 acres.”

Now the number totals over 300 acres in Oregon alone, and a chestnut growers association has been formed. Learning from scratch

Like grape vines, chestnut trees take five to seven years to begin producing. And like the pioneers who first planted grape vines in Yamhill County, the Colemans took a great leap into the unknown. Irene Coleman described it as “a real learning experience.”

For example, they learned that grafting Colossal scions to Colossal seedling trees yields truly colossal chestnuts that weigh an ounce or more. Chestnuts from ungrafted trees are puny in comparison.

They’ve learned that because chestnuts are new to the area, there aren’t any farmers or extension agents to talk to about the shot-hole borer, a tiny insect that bores into chestnut trees and infects them with a killer virus.

They’ve learned, and are educating local produce managers, that top-quality chestnuts must be stored in a cooler, like fresh vegetables, and not left out to dry, like regular nuts.

They’ve also learned how to ride out hard times such as the spring of 1992 when an orchard worker accidently sprayed their chestnut trees with herbicide. The Colemans saved the trees by lopping them off at their trunks and praying that the roots would survive.

Thankfully… They did 😉